Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The BBC’s Science Editor Rebecca Morelle goes behind the scenes with the team discovering what the melting of ice from…

The conservationist, who died aged 91 on Wednesday, challenged how we relate to the natural world.

Rats are multiplying at speed in urban areas. So, what’s really behind the boom – and is it now unstoppable?

The second Trump administration has removed more climate and environmental data from websites in the first 100 days than the…

The 14-day stoppage comes as a federal judge considers whether additional construction of the immigration detention facility in south Florida’s…

Canada is having its second worst wildfire season yet. Two scientists explain what a red air alert means and how…

Spotted lanternflies are appearing all over the East Coast. The invasive insects damage plants and trees. What should you do…

The Trump administration has asked NASA staffers to draw up plans to end at least two satellite missions that measure…

The volcano may have been primed to erupt before the magnitude 8.8 quake pushed it over the edge. (Image credit:…

Over the last six months, Americans have been inundated with a near-constant stream of announcements from the federal government — programs shuttered, funding cut, jobs eliminated, and regulations gutted. President Donald Trump and his administration are executing a systematic dismantling of the environmental, economic, and scientific systems that underpin our society. The onslaught can feel overwhelming, opaque, or sometimes even distant, but these policies will have real effects on Americans’ daily lives. In this new guide, Grist examines the impact these changes could have, and are already having, on the things you do every day. Flipping on your lights. Turning on your faucet. Paying household bills. Visiting a park. Checking the weather forecast. Feeding your family. The decisions have left communities less safe from pollution, more vulnerable to climate disasters, and facing increasingly expensive energy bills, among other changes. Read on to see how. — Katherine Bagley Your Home Flip on your lights: Pulling back from renewable energy could make your electricity bills go up. When Trump began his second term, it was with a vow to “unleash American energy.” But over the last six months, it’s become clear that this call to arms was meant strictly for fossil fuels, not the country’s booming renewable energy industry. Trump has issued a series of executive orders to revive coal production, and he has opened up millions of acres of public land to oil and gas drilling and issued a moratorium on offshore wind leases. This commitment was deepened with the Republican-led One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed into law on July 4. It bolsters investment in fossil fuels while sunsetting Biden-era credits for electric vehicles, energy efficiency, and wind, solar, and green hydrogen. Climate and clean energy advocates described the bill as “historically

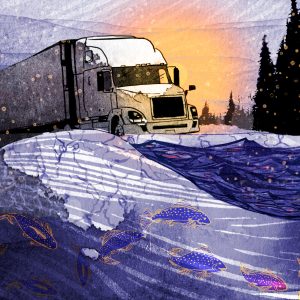

The Arctic island of Svalbard is so reliably frigid that humanity bet its future on the place. Since 2008, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault — set deep in frozen soil known as permafrost — has accepted nearly 1.4 million samples of more than 6,000 species of critical crops. But, the island is warming six to seven times faster than the rest of the planet, making even winters freakishly hot, at least by Arctic standards. Indeed, in 2017, an access tunnel to the vault flooded as permafrost melted, though the seeds weren’t impacted. This February, a team of scientists was working on Svalbard when irony took hold. Drilling into the soil, they gathered samples of bacteria that proliferate when the ground thaws. These microbes munch on organic matter and burp methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas and significant driver of global warming. Those emissions are potentially fueling a feedback loop in the Arctic: As more soil thaws, more methane is released, leading to more thawing and more methane, and on and on. Read Next Ice roads are a lifeline for First Nations. As Canada warms, they’re disappearing. Hilary Beaumont In some parts of Svalbard, though, the scientists didn’t need to drill. Air temperatures climbed above freezing for 14 of the 28 days of February, reaching 40 degrees Fahrenheit, when the average temperature at this time of year is 5 degrees. Snow vanished in places, leaving huge pools of water. “I brought my equipment to drill into frozen soil and then ended up sampling a lot of soil just with a spoon, like it was soft ice cream,” said Donato Giovannelli, a geomicrobiologist at the University of Naples Federico II and co-lead author

In the first six months of the second Trump administration, some 60,000 federal workers have been targeted for layoffs, even more have taken buyouts, and up to trillions of dollars in funding has been frozen or halted. Many more people could still be facing cuts under additional planned reductions. President Donald Trump has explicitly targeted climate- and justice-related programs and funding, but the resulting cuts have gone deep into services communities rely on to survive, like food aid in rural areas or improvements to failing wastewater infrastructure. Farmers have lost grants and support that help keep them going through increasingly volatile weather. Even your favorite YouTube creators may be affected. We asked those who have lost their federal jobs or funding to tell us about what’s being lost: What was their work providing to communities, and what happens now? Their stories, reflecting just a small sample of the many people who’ve been affected, illuminate how deep these cuts go, not only into programs explicitly working to reduce emissions, but also into those keeping us safe, healthy, fed, and informed. Have you been impacted, or know someone who has? We want to hear about it. Message us on Signal at 206-876-3147 or share your story using this form. (Learn more about how to reach us and how we will use your information.) Sort by topic All Disaster recovery Health and safety Food access Historical preservation Public information Education Data and research Waste and recycling Energy costs Disaster recovery “It offered housing, your food was paid for. I didn’t really have to worry about how I would survive.” Rachel Suber, former FEMA Corps member | Pennsylvania Read more Since

Like so much of an iceberg is hidden underwater, much of a tree is hidden underground. While the trunk and branches and leaves sequester planet-warming carbon dioxide, trees and other plants have long formed subterranean alliances with mycorrhizal fungi, which intertwine with their roots to establish a mutually beneficial trade network. In exchange for helping everything from oaks to redwoods find water and essential nutrients like nitrogen, the fungi get energy, in the form of carbon that their partners have pulled from the atmosphere. A whole lot of carbon, in fact: Worldwide, some 13 billion tons of CO2 flows from plants to mycorrhizal fungi every year — about a third of humanity’s emissions from fossil fuels — not to mention the CO2 they help trees capture by growing big and strong. Yet when you hear about campaigns to conserve and plant more trees to slow climate change, you don’t hear about the mycorrhizal fungi. Humanity may be missing the forest for the trees, in other words, in part because without going somewhere and digging, it’s hard to tell what mycorrhizal species are associating with what plants in a given ecosystem. Mycorrhizal fungi in Italy’s Apennine Mountains Seth Carnill A new research project is trying to change that. The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks, or SPUN, has launched the Underground Atlas, an interactive tool that maps mycorrhizal fungi diversity around the world. It’s a resource for scientists and conservationists to better understand where to focus on protecting these species so they can keep sequestering carbon and provide other critical services in ecosystems. “We’ve known for a long time that these mycorrhizal fungi are very important in ecosystems, and that they exist all over the planet and partner with lots of different plants,” said fungal ecologist Michael Van Nuland, lead

From Texas clear to Georgia, from the Gulf Coast on up to the Canadian border, a mass of dangerous heat has started spreading like an atmospheric plague. In the days and perhaps even weeks ahead, a high-pressure system, known as a heat dome, will drive temperatures over 100 degrees Fahrenheit in some places, impacting some 160 million Americans. Extra-high humidity will make that weather even more perilous — while the thermometer may read 100, it might actually feel more like 110. So what exactly is a heat dome, and why does it last so long? And what gives with all the extra moisture? A heat dome is a self-reinforcing machine of misery. It’s a system of high-pressure air, which sinks from a few thousand feet up and compresses as it gets closer to the ground. When molecules in the air have less space, they bump into each other and heat up. “I think about it like a mosh pit,” said Shel Winkley, the weather and climate engagement specialist at the research group Climate Central. “Everybody’s moving around and bumping into each other, and it gets hotter.” But these soaring temperatures aren’t happening on their own with this heat dome. The high pressure also discourages the formation of clouds, which typically need rising air. “There’s going to be very little in the way of cloudiness, so it’ll be a lot of sunshine which, in turn, will warm the atmosphere even more,” said AccuWeather senior meteorologist Tom Kines. “You’re just kind of trapping that hot air over one part of the country.” In the beginning, a heat dome evaporates moisture in the soil, which provides a bit of cooling. But then, the evaporation will significantly raise humidity. (A major contributor during this month’s heat dome will be the swaths of corn crops

President Trump was in Pittsburgh whipping up support for building data centers and the gas infrastructure to power them. But many worry that electricity ratepayers will get stuck with higher bills as demand for energy grows. A new online tool helps people who live near industrial facilities learn more about the chemicals and pollutants they’re being exposed to. Clean air quality advocates in Allegheny County held a virtual town hall meeting this week to push for increasing certain industrial operating fees. Business and industry leaders are talking a lot about the possibilities of AI, but the technology also comes with environmental costs. A longtime critic of the natural gas industry is leaving his post at an environmental nonprofit and recommends changing laws or making new ones. A book that asks what we can learn from going back millions of years into Earth’s history that could help us survive the climate crisis. What everyday people think about the climate-related extreme weather we've been experiencing. Swimmer's itch is a rash you can get from swimming in lakes,so researchers working in the Great Lakes have tried to eradicate it by treating ducks that carry the parasite that causes it. Nothing worked, and people have started thinking about the problem of wimmer's itch differently. It has been five years since a Pennsylvania grand jury report slammed state regulators for not protecting residents from the impacts of fracking. Advocates want Governor Josh Shapiro to do more. Environmental groups will soon be canvassing Southwestern Pennsylvania on foot, by car, and by drone in an effort to find abandoned oil and gas wells.

The next time you’re on a flight worrying about destroying the planet, rest easy knowing that at least you’re not in a fighter jet. The airline industry is responsible for 2.5 percent of global CO2 emissions, but the world’s militaries are responsible for more than double that, at 5.5 percent. When nations boost military budgets, they also boost their carbon emissions. With a bump of $157 billion, thanks to the budget the Trump administration passed earlier this month, the United States now spends $1 trillion each year on defense. That’s more than three times as much as China, the next highest spender, as well as the entire European Union. If combined, the world’s armed forces would have the fourth highest carbon footprint, behind India, the U.S., and China. Yet it’s been maddeningly difficult for researchers to monitor the emissions of militaries, which aren’t required to report these things. “There’s a guessing game involved,” said Nick Buxton, who has coauthored reports on military emissions from the Transnational Institute, an international research and advocacy group. “One of the overwhelming calls for everyone working in the sector is just for more open and transparent data, so we can come up with some reliable figures.” To that end, using what data the Department of Energy has made publicly available between 1975 to 2022, researchers have calculated that if the U.S. consistently decreased military spending — by even a little — instead of increasing it, it’d be saving as much energy as Delaware and Slovenia use in a year. A decrease of less than 7 percent each year over about a decade would theoretically reduce energy consumption from about 640 trillion to 394 trillion British thermal units (a measurement of heat energy produced from burning fuels). The study gives observers not just a better idea

This coverage is made possible through a partnership between Grist and Verite News, a nonprofit news organization with a mission to produce in-depth journalism in underserved communities in the New Orleans area. As thousands of architects and planners flocked to New Orleans in 2014 for the world’s largest sustainable design conference, the city saw a chance to prove it belonged in the green building big leagues. City leaders announced at the Greenbuild International Conference and Expo that New Orleans would join Minneapolis, Seattle, and a vanguard of other cities in developing a program requiring large building owners to track and disclose their energy use. New Orleans’ embrace of “energy benchmarking” drew praise at the conference, with one green building expert declaring that the city was “paving the way” for the rest of the country to follow. But New Orleans lost momentum, waiting more than a decade before finally approving its benchmarking ordinance on Thursday. In the meantime, New Orleans fell behind about 50 other cities that have approved energy tracking and disclosure requirements for most large buildings. “The benchmarking ordinance — finally!” New Orleans City Councilmember Helena Moreno said. “After many, many years, we’re finally getting there.” Benchmarking can both shame the power hogs and extol the virtues of the frugal. The data spurs investment in older, inefficient buildings and encourages more climate-conscious design in new ones, advocates say. “It’s well understood that one cannot change what one does not measure,” said Christopher Johnson, a board member with the New Orleans chapter of the American Institute of Architects. By passing the ordinance, the city is “empowering owners to take matters into their own hands to improve their buildings.” Buildings are responsible for 40 percent of total energy use in the U.S., and about 35 percent of the country’s carbon emissions, according

The U.S. is exporting more natural gas than ever before. Now, the Biden administration is pausing new projects. Here’s what…

Malesuada fames ac turpis egestas integer. Quam nulla porttitor massa id neque aliquam vestibulum morbi blandit. Commodo sed egestas egestas…

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. In…